Bangladesh. Cina ed il ponte sul Padma. (Sempre attivi , i cinesi)

Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2018-05-07.

Il Bangladesh è un paese disperatamente povero. Disperatamente.

Tuttavia qualcosa sembrerebbe iniziare a muoversi.

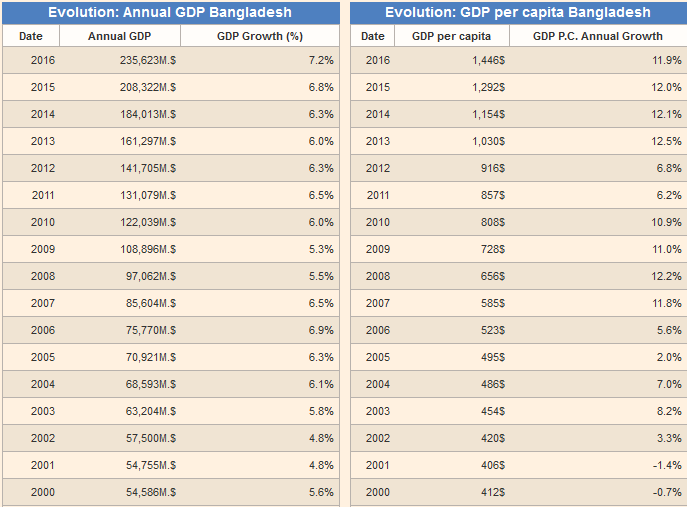

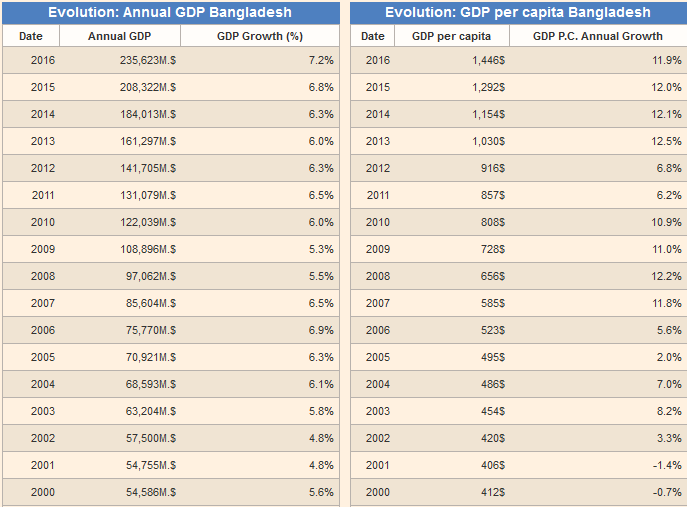

Se nel 2000 il pil procapite era 412 Usd, a fine 2016 era salito a 1,446. Negli ultimi cinque anni il pil è cresciuto al ritmo di qualcosa di più del 10% all’anno.

«On 4 October 2000, the Government of Bangladesh issued a postal stamp marking the 25th anniversary of the establishment of Bangladesh-China diplomatic relations. By this time, China had provided economic assistance totaling US$300 million to Bangladesh and the bilateral trade had reached a value mounting to a billion dollars. In 2002, the Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao made an official visit to Bangladesh and both countries declared 2005 as the “Bangladesh-China Friendship Year.” ….

The two countries signed nine different bi-lateral agreements to increase there mutual relationship. ….

On Bangladesh Nationalist Party PM Begum Khaleda Zia’s invitation China was added as an observer in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). After Cyclone Sidr hit Bangladesh in 2007, China donated US$1 million for relief and reconstruction in cyclone-hit areas. ….

Bangladesh is third largest trade partner of China in South Asia. But, the bilateral trade between them is highly tilted in favour of Beijing. Bilateral trade reached as high as US$3.19 billion in 2006, reflecting a growth of 28.5% between 2005 and 2006. China has bolstered its economic aid to Bangladesh to address concerns of trade imbalance; in 2006, Bangladesh’s exports to China amounted only about USD 98.8 million. Under the auspices of the Asia-Pacific Free Trade Agreement (AFTA), China removed tariff barriers to 84 types of commodities imported from Bangladesh and is working to reduce tariffs over the trade of jute and textiles, which are Bangladesh’s chief domestic products. China has also offered to construct nuclear power plants in Bangladesh to help meet the country’s growing energy needs, while also seeking to aid the development of Bangladesh’s natural gas resources. China’s mainly imports raw materials from Bangladesh like leather, cotton textiles, fish, etc. China’s major exports to Bangladesh include textiles, machinery and electronic products, cement, fertiliser, tyre, raw silk, maize, etc» [Fonte]

*

«Two Bangladeshi and two Chinese firms have signed two joint venture pacts to build over 100 km rail lines and required infrastructure in the country’s southeastern Cox’s Bazar district bordering Myanmar.

Officials of Bangladesh Railways and joint venture China Railway Group Limited (CREC) of China and Toma Construction and Company Limited of Bangladesh; and China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) and MAX JV (joint adventure of CCECC of China and MAX international Ltd of Bangladesh) signed the deals on behalf of their respective sides here on Saturday. …. the project is part of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) support»

«The Export-Import Bank of China is going to fund the rail connection in Bangladesh’s largest infrastructure project till date, the Padma Bridge. …. Once in operation, it will only take about three and a half hours to travel to Khulna from Dhaka …..

This will help expansion of the transport sector, trade and commerce. This route will also be connected with the trans-Asian railway ….

Project sources said the principal works involve constructing 169 kilometres of main line, 43.33km loop and siding, laying down 215.22km broad gauge rail truck, 23.37km viaduct and 1.98km ramps.

Other works include constructing 66 big bridges, 244 small bridges and culverts, a highway overpass, 29 level crossings, 40 underpasses, 14 new station building, development of six existing stations, and arranging computer-based railway interlock system signalling at 20 stations»

*

«The Padma Bridge is a multipurpose road-rail bridge across the Padma River under construction in Bangladesh. It will connect Louhajong, Munshiganj to Shariatpur and Madaripur, linking the south-west of the country, to northern and eastern regions. Padma Bridge is the most challenging construction project in the history of Bangladesh. The two-level steel truss bridge will carry a four-lane highway on the upper level and a single track railway on a lower level. With 150 m span, 6150 m total length and 18.10 m width it is going to be the largest bridge in the Pawdda-Brahmaputra-Meghna river basins of country in terms of both span and the total length» [Fonte]

*

Il ponte sul Padma costerà alla fine 3.8 miliardi di dollari americani.

Basta solo guardare la carta geografica per comprendere quanto sia essenziale un ponte degno di tal nome sul Padma, un fiume di portata quasi eguale a quella del Rio delle Amazzoni.

*

Orbene.

Lasciamo i Lettori alla lettura dell’articolo comparso su Project Syndicate.

«To what does Bangladesh owe its quiet transformation? As with all large-scale historical phenomena, there can be no certain answers, only clues. Still, in my view, Bangladesh’s economic transformation was driven in large part by social changes, starting with the empowerment of women.»

Elementare, si direbbe.

Gli investimenti cinesi, strade, ponti, infrastrutture, etc, a ben poco sarebbero serviti, se non quasi a nulla.

È stata la liberazione femminile a generare l’inizio di questa ripresa economica.

Il farsesco è che il Project Syndicate è letto anche in Cina ed in Bangladesh.

*

Una sola domanda.

Il Bangladesh sarà più riconoscente all’Occidente oppure alla Cina?

Nota.

Il nome Padma denomina gli ultimi 145 kilometri dopo la confluenza del Padma Superiore e del Brahmaputra, fiume che nasce dal Tibet ed è lungo 2,900 kilometri.

As a result of progressive social policies and a bit of historical luck, Bangladesh has gone from being one of the poorest countries in South Asia to an aspiring “tiger” economy. But can it avoid the risk factors that have derailed dynamic economies throughout history?

*

NEW YORK – Bangladesh has become one of Asia’s most remarkable and unexpected success stories in recent years. Once one of the poorest regions of Pakistan, Bangladesh remained an economic basket case – wracked by poverty and famine – for many years after independence in 1971. In fact, by 2006, conditions seemed so hopeless that when Bangladesh registered faster growth than Pakistan, it was dismissed as a fluke.

Yet that year would turn out to be an inflection point. Since then, Bangladesh’s annual GDP growth has exceeded Pakistan’s by roughly 2.5 percentage points per year. And this year, its growth rate is likely to surpass India’s (though this primarily reflects India’s economic slowdown, which should be reversed barring gross policy mismanagement).

Moreover, at 1.1% per year, Bangladesh’s population growth is well below Pakistan’s 2% rate, which means that its per capita income is growing faster than Pakistan’s by approximately 3.3 percentage points per year. By extrapolation, Bangladesh will overtake Pakistan in terms of per capita GDP in 2020, even with a correction for purchasing power parity.

To what does Bangladesh owe its quiet transformation? As with all large-scale historical phenomena, there can be no certain answers, only clues. Still, in my view, Bangladesh’s economic transformation was driven in large part by social changes, starting with the empowerment of women.

Thanks to efforts by the nongovernmental organizations Grameen Bank and BRAC, along with more recent work by the government, Bangladesh has made significant strides toward educating girls and giving women a greater voice, both in the household and the public sphere. These efforts have translated into improvements in children’s health and education, such that Bangladeshis’ average life expectancy is now 72 years, compared to 68 years for Indians and 66 years for Pakistanis.

The Bangladesh government also deserves credit for supporting grassroots initiatives in economic inclusion, the positive effects of which are visible in recently released data from the World Bank. Among Bangladeshi adults with bank accounts, 34.1% made digital transactions in 2017, compared to an average rate of 27.8% for South Asia. Moreover, only 10.4% of Bangladeshi bank accounts are “dormant” (meaning there were no deposits or withdrawals in the previous year), compared to 48% of Indian bank accounts.

Another partial explanation for Bangladesh’s progress is the success of its garment manufacturing industry. That success is itself driven by a number of factors. One notable point is that the main garment firms in Bangladesh are large – especially compared to those in India, owing largely to different labor laws.

All labor markets need regulation. But, in India, the 1947 Industrial Disputes Act imposes heavy restrictions on firms’ ability to contract workers and expand their labor force, ultimately doing more harm than good. The law was enacted a few months before the August 1947 independence of India and Pakistan from British imperial rule, meaning that both new countries inherited it. But Pakistan’s military regime, impatient with trade unions from the region that would become Bangladesh, repealed it in 1958.

Thus, having been born without the law, Bangladesh offered a better environment for manufacturing firms to achieve economies of scale and create a large number of jobs. And though Bangladesh still needs much stronger regulation to protect workers from occupational hazards, the absence of a law that explicitly curtails labor-market flexibility has been a boon for job creation and manufacturing success.

The question is whether Bangladesh’s strong economic performance can be sustained. As matters stand, the country’s prospects are excellent, but there are risks that policymakers will need to take into account.

For starters, when a country’s economy takes off, corruption, cronyism, and inequality tend to increase, and can even stall the growth process if left unchecked. Bangladesh is no exception.

But there is an even deeper threat posed by orthodox groups and religious fundamentalists who oppose Bangladesh’s early investments in progressive social reforms. A reversal of those investments would cause a severe and prolonged economic setback. This is not merely a passing concern: vibrant economies have been derailed by zealotry many times throughout history.

For example, a thousand years ago, the Arab caliphates ruled over regions of great economic dynamism, and cities like Damascus and Baghdad were global hubs of culture, research, and innovation. That golden era ended when religious fundamentalism took root and began to spread. Since then, a nostalgic pride in the past has substituted for bold new pursuits in the present.

Pakistan’s history tells a similar tale. In its early years, Pakistan’s economy performed moderately well, with per capita income well above India’s. And it was no coincidence that during this time, cities like Lahore were multicultural centers of art and literature. But then came military rule, restrictions on individual freedom, and Islamic fundamentalist groups erecting walls against openness. By 2005, India surpassed Pakistan in terms of per capitaincome, and it has since gained a substantial lead.

But this is not about any particular religion. India is a vibrant, secular democracy that was growing at a remarkable annual rate of over 8% until a few years ago. Today, Hindu fundamentalist groups that discriminate against minorities and women, and that are working to thwart scientific research and higher education, are threatening its gains. Likewise, Portugal’s heyday of global power in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries passed quickly when Christian fanaticism became the empire’s driving political force.

As these examples demonstrate, Bangladesh needs to be vigilant about the risks posed by fundamentalism. Given Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s deep commitment to addressing these risks, there is reason to hope for success. In that case, Bangladesh will be on a path that would have been unimaginable just two decades ago: toward becoming an Asian success story.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento