Europa. Il problema italiano. Default oppure exit.

Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2019-03-13.

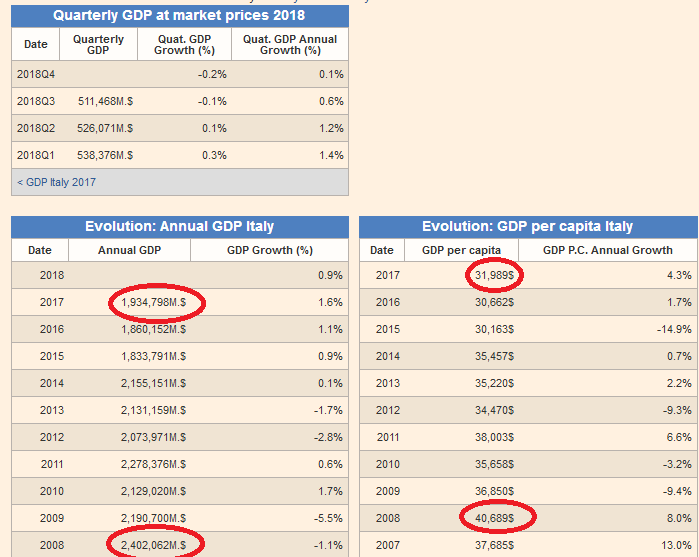

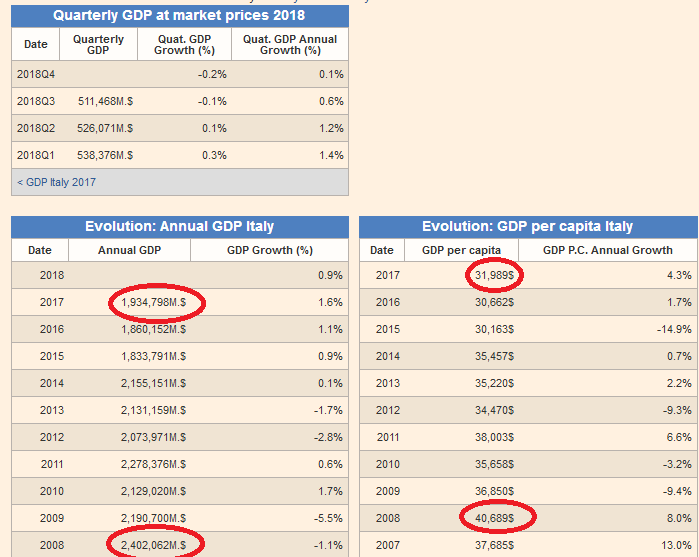

La Tabella riprodotta in fotocopia dovrebbe essere eloquente.

Nel 2008 il Pil espresso in Usd era 2,402 miliardi Usd, nel 2017 ammontava a 1,934.

Sempre nel 2008 il Pil procapite era di 40,689 Usd, mentre a fine 2017 ammontava a 31,989 Usd. Un perdita del 25% circa.

Nel 2008 il debito sovrano era 1,666 miliardi di euro, e nel 2017 era 2,283 miliardi di euro.

Nel volgere di dieci anni i Governi nazionali hanno aumentato il debito pubblico di 617 miliardi. Ma questa immane cifra non è stata utilizzata per investimenti nel comparto produttivo, che poi rendono reddito, bensì in partite correnti: pensioni, sussidi, e così via.

Né, tanto meno, è stata utilizzata per mettere in atto riforme strutturali dello stato, ossia per delegiferate, deburocratizzare, ridurre il numero e le mansioni dei dipendenti pubblici, e per ridurre imposte e tasse.

Le responsabilità di quanti abbiano governato in quell’arco di tempo si configurano come alto tradimento.

E le conseguenze iniziano a farsi sentire con mano pesante.

* * * * * * *

«Crisis brewing in Italy will lead to default, exit from the euro, or both»

*

«There is a dual Italian crisis brewing in the European Union.»

*

«On the one hand, it is a political, or even geopolitical, crisis. Italy is undermining the unity of the European Union; blocking the EU’s recognition of those behind the coup in Venezuela as the legitimate authority; preventing the expansion of sanctions against Russia; and even supporting the ‘yellow vest’ movement in France, which is arousing the anger of the French government.»

*

«On the other hand, the crisis is economic in nature. Italy is once more sliding into a recession (economic growth was negative in the country); Italian banks are again facing financial problems; and the business media has already estimated that the Italian economic crisis could blow up the entire European banking system.»

* * * * * * * * * * *

«There is a strong possibility that the EU’s leaders will soon be faced with a choice: try to save Italy (and the whole of Europe) from yet another crisis or set an example by punishing the Italian government for the country’s independent economic and foreign policies»

*

«bad bank debts of €185 billion were reported in Italy at the end of 2017 – a record for the European Union»

*

«Italy accounts for roughly a quarter of the non-performing loans in the eurozone»

*

«Conte’s cabinet is once again facing a dilemma: either put up with the economic stranglehold by EU bureaucrats (and voter dissatisfaction) or go up against the European Union»

*

«To really understand the Italian problem, it should be borne in mind that, as a member of the European Union and the eurozone, Italy does not have full national sovereignty, especially when it comes to economic matters»

*

«It is clear that conflicts like these indicate political instability within the European Union and the situation is becoming truly volatile»

*

«On the other hand, if this happened then Italy could well declare either a default on its government debt, or its exit from the eurozone, or (as noted by The Telegraph) both at the same time»

* * * * * * * * * * *

«Ironically, the worse hit by such a scenario will be French banks, which Bloomberg estimates have Italian loans worth hundreds of billions of euros on their balance sheets. What’s more, such a shock could see foreign investors (and many European ones) beginning to flee the eurozone, adding a currency component to the banking crisis.»

*

«“the winds of change have crossed the Alps”. For those who lived through the collapse of the USSR, the symbolism of the Italian politician’s phrase, whether intentional or not, cannot but evoke certain associations with what was said in the Soviet information space in the 1980s»

*

«Populist politicians in Europe love comparing the European Union to the late USSR, and this comparison is starting to ring true like never before.»

* * * * * * * * * * *

Bene.

Questa è la situazione che i numeri esprimono, e che sarebbe bene rileggerseli ed impararli a memoria.

L’Italia è nella situazione dell’Unione Sovietica a fine degli anni ’80, e sta seguendo le orme della Grecia.

There is a dual Italian crisis brewing in the European Union. On the one hand, it is a political, or even geopolitical, crisis. Italy is undermining the unity of the European Union; blocking the EU’s recognition of those behind the coup in Venezuela as the legitimate authority; preventing the expansion of sanctions against Russia; and even supporting the ‘yellow vest’ movement in France, which is arousing the anger of the French government.

On the other hand, the crisis is economic in nature. Italy is once more sliding into a recession (economic growth was negative in the country); Italian banks are again facing financial problems; and the business media has already estimated that the Italian economic crisis could blow up the entire European banking system.

There is a strong possibility that the EU’s leaders will soon be faced with a choice: try to save Italy (and the whole of Europe) from yet another crisis or set an example by punishing the Italian government for the country’s independent economic and foreign policies. In turn, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte’s government will most likely have its own dilemma to deal with: bow down and sell its principles to get help from Brussels or go all out and regain Italian independence. The choice will not be easy and either decision will be painful. Neither ending to this Italian drama could really be called happy. As this headline in The Telegraphquite rightly notes: “Crisis brewing in Italy will lead to default, exit from the euro, or both.”

At the heart of the Italian issue is the fact that the 2008 crisis never really went away, and all the self-congratulations of European (especially Italian) politicians were actually attempts to hide the old, unresolved problems under the carpet. Until recently, the Italian economy had been showing anaemic growth, but it began to decline over the last two quarters. Efforts to borrow more are not helping, either. There are negative interest rates in the eurozone, but it is often more profitable for banks to keep their money in the European Central Bank (even at a negative interest rate) or invest it somewhere outside of Italy than lend it to risky Italian businesses and ordinary Italians who will probably never pay the money back. Indeed, bad bank debts of €185 billion were reported in Italy at the end of 2017 – a record for the European Union. Italy accounts for roughly a quarter of the non-performing loans in the eurozone (i.e. loans that are not being repaid or are seriously overdue), and it is easy to see why Brussels considers the country to be the EU’s weak spot.

Another problem developed after the Conte government – a coalition of two populist, eurosceptic parties – came to power in June 2018. It tried to solve the country’s economic issues by increasing government incentives, but Italy is already in debt (Italy’s national debt is 131 per cent of its GDP). The European Commission warned it against enlarging its budget deficit and increasing its national debt too much, and threatened fines for violating budget discipline.

In light of the European Commission’s threat of economic sanctions (!), the Italian government had to negotiate and make concessions in its fiscal policy, and now, due to Italy’s shrinking economy, Conte’s cabinet is once again facing a dilemma: either put up with the economic stranglehold by EU bureaucrats (and voter dissatisfaction) or go up against the European Union.

To really understand the Italian problem, it should be borne in mind that, as a member of the European Union and the eurozone, Italy does not have full national sovereignty, especially when it comes to economic matters. It does not control the monetary policy of the European Central Bank and cannot even prepare a budget in line with the wishes of its own government or parliament without the risk of running into sanctions or fines from the European Commission. What’s more, Italian eurosceptic politicians suspect that the European Commission (in which the main roles belong to people hand-picked by Germany, France and the US) is punishing Italy and literally strangling its economy because of a political dislike of the Italian government’s geopolitical actions.

Take Rome’s recent move to block the European Union’s recognition of Juan Guaidó as the president of Venezuela, for example. It makes sense that pro-US officials in the European Commission would try to punish Italy as harshly as possible for such behaviour. And Italy’s démarches are not limited to Venezuela. One of the leaders of the government coalition, Deputy Prime Minister of Italy Luigi Di Maio, held a meeting this week with the leaders of the ‘yellow vest’ movement in France and supported their efforts, a move that caused great offence in the government of President Macron, who probably regarded such actions by the Italian authorities as an attempt to legitimise the political demands of a movement set on removing him from power. The French president’s logical response to such actions by the Italian government is to use the European Commission and its budgetary leverage to put pressure on Italy.

It is clear that conflicts like these indicate political instability within the European Union and the situation is becoming truly volatile. On the one hand, the European Commission really could push Italy to the brink of bankruptcy or even trigger a full-blown economic collapse, which would probably (but far from definitely) lead to a change of government in Rome. On the other hand, if this happened then Italy could well declare either a default on its government debt, or its exit from the eurozone, or (as noted by The Telegraph) both at the same time, especially since such threats (right up to the country’s withdrawal from the European Union) have already been made by the government, the unofficial leader of which is Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini.

Ironically, the worse hit by such a scenario will be French banks, which Bloomberg estimates have Italian loans worth hundreds of billions of euros on their balance sheets. What’s more, such a shock could see foreign investors (and many European ones) beginning to flee the eurozone, adding a currency component to the banking crisis. Time will tell whether the European Commission is willing to take such risks to punish Italy’s freedom-loving politicians, but we can already agree with Luigi Di Maio, who, after meeting the French ‘yellow vests’, declared that “the winds of change have crossed the Alps”. For those who lived through the collapse of the USSR, the symbolism of the Italian politician’s phrase, whether intentional or not, cannot but evoke certain associations with what was said in the Soviet information space in the 1980s. At that time, the “winds of change” were blowing through every single crack in the Soviet Union, and we know it never ends well. Populist politicians in Europe love comparing the European Union to the late USSR, and this comparison is starting to ring true like never before.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento