Germania. Seehofer. Concentra i migranti in ‘Centri di Asilo’.

Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2018-04-02.

«Germany’s new interior minister, Horst Seehofer, wants to open the first so-called “anchor center” in the autumn»

*

«Many migrants are to be housed there from arrival to deportation»

*

«In Bavaria, one model “reception center” is home to more than 1,300 asylum-seekers»

*

«Directors say the barbed-wire enclosure and lack of privacy are for “safety” and efficiency»

* * *

L’idea di concentrare i migranti nelle caserme dismesse sembrerebbe essere di ragionevole buon senso.

Sono strutture usualmente vicine a grandi città, dotate di tutti i servizi necessari, dalla rete nera a quella bianca, con cucine di idonea capacità e locali mensa puliti, pulibili e spaziosi. Di norma poi hanno un giardinetto attorno.

Di certo queste strutture non consentono troppa privacy, ma le caserme non sono succursali della catena Hilton.

Sorge a questo punto spontanea una domanda. Sarebbe davvero troppo chiedere ai signori migranti di tenere puliti quei locali che i tedeschi hanno loro affidati lindi? In fondo, poi, ci vivono loro, mica Frau Merkel.

Dalle lamentele fatte, sembrerebbe doversi dedurre che in Africa quei migranti avevano dimore da gran signori.

*

Ma ci voleva proprio Herr Seehofer per prendere un simile provvedimento?

Germany’s new interior minister, Horst Seehofer, wants to open the first so-called “anchor center” in the autumn. Many migrants are to be housed there from arrival to deportation. But police are skeptical.

*

Interior Minister Horst Seehofer is pressing ahead with his “masterplan” to speed up deportations of asylum seekers and refugees and streamline asylum procedures.

Deputy Minister Stephan Mayer told German daily Süddeutsche Zeitung that opening a so-called “anchor center” in time for the Bavarian state elections in mid-October had “the highest priority.”

“I’m confident that we can present more detailed plans after the Easter weekend,” he told the paper.

Controversial ‘masterplan’

Under plans presented by Seehofer when he took over as interior minister, these so-called “anchor centers” are designed to house asylum seekers from their arrival in Germany until their possible deportation. The first one is likely to be built in Bavaria.

Seehofer – who recently said that Islam is not part of Germany but Muslims are – has stressed, however, that no one should stay in the centers for more than 18 months and that migrants who are likely to be able to stay in Germany should be allowed to move on from the centers.

Police skeptical

Germany’s federal police would ultimately be in charge of the centers as they are responsible for deportations as well as protecting Germany’s borders.

Seehofer’s aim is to get the federal police more involved in asylum procedures to relieve local and regional authorities.

But police representatives have expressed criticism of the plans, insisting that it is not the federal police’s responsibility to ensure security at such centers. Jörg Radek of the Police Union (GdP) has called the plans illegal, as it’s not the federal police’s responsibility to “police asylum seekers.”

“We don’t train police officers to run prisons,” he told the DPA news agency, adding that he sees the jucidiary and the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) as responsible.

He explained that these centers would fall under the category of “measures that curtail freedom of movement,” whereas the federal police’s main responsibility is to “avert danger.”

Plan hinders integration

Local councils also point out that keeping people in large, often cramped, centers can lead to violence and prevent migrants from getting a chance to integrate in Germany.

In Bavaria, one model “reception center” is home to more than 1,300 asylum-seekers. Directors say the barbed-wire enclosure and lack of privacy are for “safety” and efficiency. One resident says “it’s a wasted life.”

*

Is this what the future of asylum management will look like in Germany? On the outskirts of the romantic UNESCO World Heritage city of Bamberg in Bavaria, one passes through an unforgiving security checkpoint manned by tough guards to enter into a facility lined with barbed wire. This was once a US army base, complete with cinema, supermarket and disco.

Since July 2016 the long, light-colored barracks have served as refugee housing. The streets are named after types of trees. During my visit in December, a thin man in a track suit stood at a roundabout and waved: “I tell you the truth!” he yelled to me. There are guards everywhere. Welcome to the Upper Franconia Reception Center (AEO).

Stefan Krug didn’t need a key as he entered the first-floor apartment. That is the way things are everywhere throughout the facility, not just in the model apartment. “We do that for residents’ security,” said Krug, who heads Upper Franconia’s asylum affairs department.

The apartment has a parquet floor, a balcony, toilet, bathroom, living room and four bedrooms. There is an electric kettle in the kitchen. “Up to 16 people live in the biggest apartments,” Krug said. That sounds crowded. “We have calculated that it provides each inhabitant with 7.1 square meters (76.5 square feet) of space. That meets the Social Ministry’s guidelines for collective accommodations,” he added. Fulfilled guidelines are the goal of every bureaucracy.

Krug said his office was doing its best to make living together as beneficial as possible for all involved. “We pay close attention to homogeneity and to cultural proximity,” he said. “We also leave families together,” he added. He and his team are very happy with the results so far.

‘State of the art’

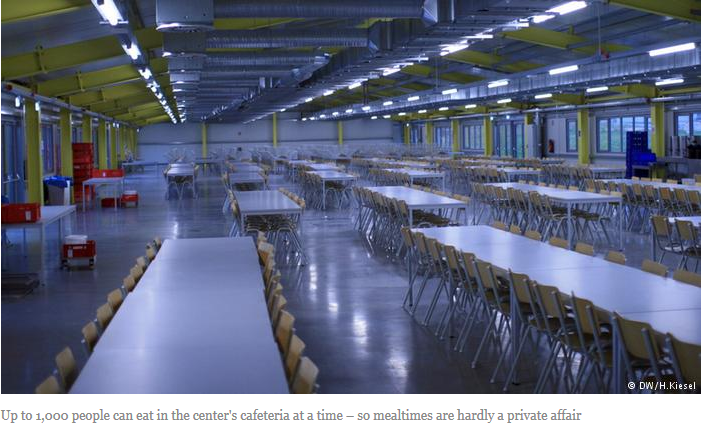

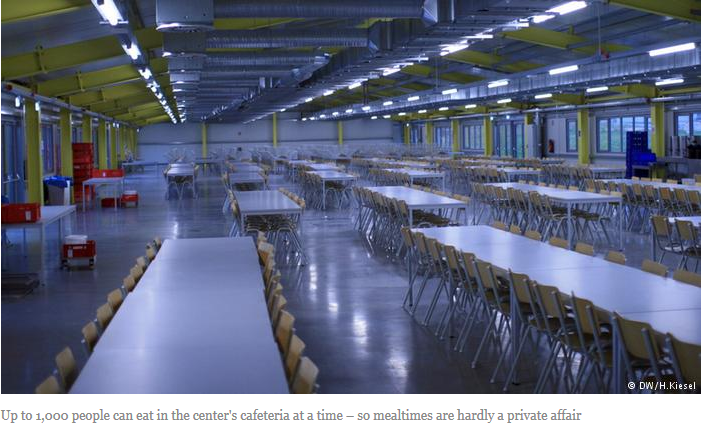

When it is time to eat, residents head over to the cafeteria. It is an enormous hall with yellow steel girders, from which an impressive ventilation system hangs. That system is necessary: Up to 1,000 people can eat here at one time. Food is halal (permissible according to Islamic law) and even vegan upon request.

The way the government sees things, the Upper Franconia Reception Center provides refugees with everything they need. They can even receive text notifications about the status of their asylum applications, which they submit at the facility, on their cellphones.

The Federal Administrative Court has an office here, as does the region’s immigration agency. The welfare agency is in Block E. This is all “state of the art” in Krug’s eyes: “If the government decides to put refugees into centralized accommodations, then our facility is definitely a good model.”

Controversial proposal by interior minister

That is exactly the plan advocated by Horst Seehofer, the interior minister in the new federal government and a member of Bavaria’s conservative Christian Social Union (CSU). He has presented plans to open “anchor centers” to house asylum applicants from their arrival in Germany until their requests are granted or they are deported. And the first one may well be built in Bavaria. The centers that Seehofer proposes are intended to provide efficiency, as well as maximum control over the people who come to Germany hoping to find more sustainable living conditions.

Seehofer has for years presented a hard line on immigration and frequently come into conflict with German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Whether the Bamberg model will be replicated elsewhere remains to be seen. In the wake of various controversies, on Wednesday state Interior and Integration Minister Joachim Hermann announced that Bavaria would reduce the maximum number of residents at the center to 1,500, down from the currently permitted 3,400, and shut the facility permanently in 2025.

Good for some, a dead end for others

Many of the people who live at the center are less convinced about the model character of the facility. At noon on that December day, the central streets begin to fill up with residents on their way to the cafeteria. The man from the roundabout who had promised me the truth was in the crowd. “I’m Adel, from Casablanca,” he said.

Adel said things were bad: The guards are rough and the food is awful. A group of young men, fellow Moroccans, gathered around. They nodded in agreement. “We can do a lot of things — just give us a chance!” Adel shouted. He said he wasn’t giving up hope, but added: “I just got a denial.” It was only a matter of time before he would be deported, and that was time that he would have to spend at the center.

It is quite possible that residents who have been denied asylum are especially eager to complain about living conditions at the facility because they are frustrated.

“One can certainly expect people to spend a couple of weeks here,” said Markus Ziebarth, a social worker who runs the asylum and social counseling office set up by the Catholic relief organization Caritas at the center.

But, he said, some people have been stuck here for months. “They can’t lock their doors, they don’t have any privacy, and they cannot structure their own lives,” he said.

Ziebarth thinks the situation would be easier to organize if residents were in smaller units. Nevertheless, he said, “one also has to take into account that this is a big challenge for the city of Bamberg and its 70,000 residents.”

The challenge surfaced publicly in January, when about 100 local residents, including refugees who live at the center, marched to Bamberg’s city hall to protest the conditions. The government of Upper Franconia continues to call the living conditions for the current 1,376 refugees at the center “humane.”

Refugee shuttle to the historic city center

City administrators have tried to mitigate the problems that the refugee center has been blamed for. An hourly bus heads straight from the facility to the picturesque historic city center.

Residents and business owners along the street leading into town complained about refugees before the buses started running. Police reported that petty crime had gone up in the area. Now, city residents no longer seem to be very interested in establishing contact with those seeking protection here. The bus fills up fast, security agents from the refugee center scan passengers’ ID cards, and off they go.

David stood next to the stop and watched as the green bus pulled away from the curb. “I usually stay here and walk my rounds in the camp,” the 37-year-old from Ghana said. He cannot shop anyhow: He doesn’t have any money. He hasn’t heard a decision on his asylum status and is still hoping for the best. Most of his compatriots are denied asylum. “I pray that Germany’s economy keeps growing,” he said, “because I want to stay here.”

That is a dream that Khady from Senegal no longer has. She approached slowly: “I have been here for a year already. I was denied asylum.” She was waiting to be deported but that is not so easily with Senegal.

Life in the refugee camp after you have been denied asylum isn’t easy either: People who have been denied asylum receive no money, and that translates into problems with other residents and with guards. Summing up her daily routine, Khady said: “You can’t leave. You aren’t allowed to work. It’s a wasted life.”

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento