Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2018-12-18.

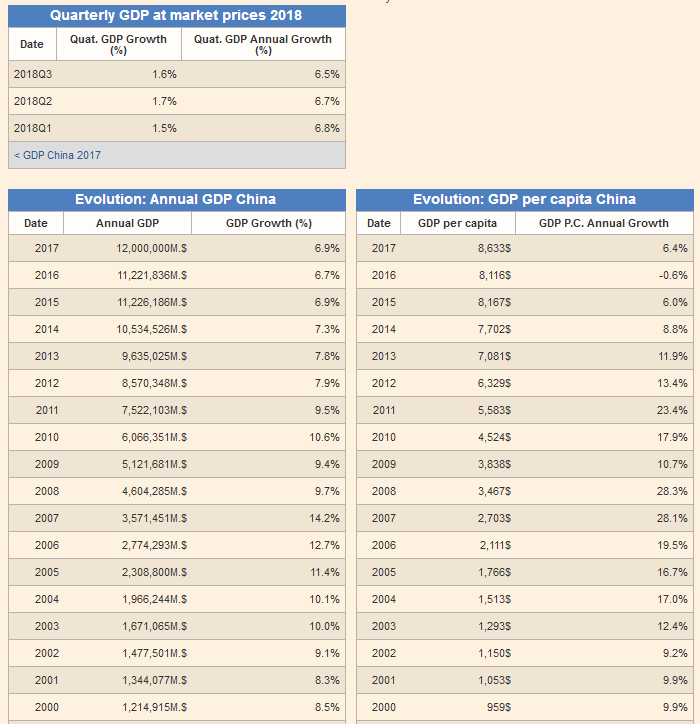

Mentre negli ultimi trenta anni l’Occidente ha proseguito a baloccarsi con le ideologie, la Cina è passata da un pil procapite di 349$ nel 1990 agli 8,663$ del 2017: è aumentato di venticinque volte.

Ma se si desse una sbirciata al futuro prossimo, le sorprese sarebbero ancora maggiori.

International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook (October – 2017)

Le proiezioni al 2022 danno la Cina ad un pil ppa di 34,465 (20.54%) miliardi di Usd, gli Stati Uniti di 23,505 (14.01%), e l’India di 15,262 9.10%) Usd. Seguono Giappone con 6,163 (3.67%), Germania (4.932%), Regno Unito 3,456 (2.06%), Francia 3,427 (2.04%), Italia 2,677 (1.60%). Russia 4.771 (2.84%) e Brasile 3,915 (2.33%).

I paesi del G7 produrranno 46,293 (27.59%) mld Usd del pil mondiale, mentre i paesi del Brics renderanno conto di 59,331 mld Usd (35.36%).

*

La ricetta economica messa in opera da Mr Deng Xiaoping è di una semplicità sconcertante:

«“What the government needs to do is to remove the straitjacket still stifling entrepreneurs. There are still too many rules, stupid rules. The going is getting tougher. Hopefully that would shake off some of the bureaucratic complacency.”»

Deng Xiaoping era la quintessenza del pragmatismo cinese, cui non interessa il colore del gatto, purché acchiappi i topi. Ciò che interessa è il ritorno prestazione/costo. Così convivono proficuamente azioni che per gli occidentali sarebbero contrastanti perché ascrivibili ad ideologie differenti ed opposte.

«Deng Xiaoping restarted university entrance examinations in late 1977, allowing all students to compete for a college place».

Nello stesso anno fece internare nel Laogai circa 600,000 insegnanti assunti nella scuola per meriti politici. Scuola epurata, scuola funzionante.

Con la stessa nonchalance lasciava totalmente libere le persone con l’ordine di arricchirsi più che potessero, e nel contempo procedeva a nazionalizzare delle aziende: azioni anche questa per gli occidentali fuori dal ben del’intelletto.

Ma quello che l’occidente non può costituzionalmente comprendere è che in Cina la politica la si fa in quella scuola mandarinica ora denominata partito comunista cinese. Il termine ‘comunista‘ ha in occidente un senso del tutto differente da quello che ha in Cina.

Altre cose che fanno impazzire gli occidentali?

Cina. L’Islam sarebbe una patologia psichiatrica, e così la si cura.

Cinesi, gente pratica. Risolto il problema dell’integralismo islamico.

«Chinese authorities in the far-northwestern region of Xinjiang on Wednesday revised legislation to permit the use of “education and training centers” to combat religious extremism.»

*

«In practice, the centers are internment camps in which as many as 1 million minority Muslims have been placed in the past 12 months»

* * *

Sorriso e bonomia di Mr Xi potrebbero trarre in inganno: non si scambi la tradizionale semplicità e cortesia cinese per mancanza di polso. Gli uiguri ed i kazaki non vogliono essere ragionevoli?

Nessun problema.

Resteranno nel laogai fino a tanto che non parleranno fluentemente il cinese mandarino.

* * * * * * *

L’Occidente però non ha proprio imparato nulla dalla Cina.

«Deng’s reforms, officially launched 40 years ago on Dec. 18 at a meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, precipitated one of the greatest creations of wealth in history, lifting more than 700 million people out of poverty.»

*

«But the changes also sowed the seeds of many of the problems China faces today»

*

«Two decades of growth at any cost under Presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao starting in 1993 saddled the nation with polluted rivers and smoggy skies, plus a mountain of debt»

*

«But while Deng wanted his market-based reforms to make China rich, Xi has reasserted the control of the state in an effort to turn the country into a political and technological superpower»

*

Da un personaggio che ha trovato semplicemente logico mettere in campo di lavoro un milione di persone non ci si aspetterebbero grossi scrupoli per i problemi ecologici che così stanno a cuore agli Occidentali: Xi vuole solo il dominio del mondo, e, come si dice, Parigi val bene una Messa.

→ Bloomberg. 2018-12-17. China Built a Global Economy in 40 Years. Now It Has a New Plan

Deng’s 1978 reforms gave China economic might. Now Xi wants more.

*

Fred Hu will never forget the terror in his science teacher’s eyes when the man was dragged away to a Chinese jail during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. Then a 12-year-old peeping into the classroom, his dream of escaping rural poverty to become a journalist or teacher seemed hopeless.

Two years later, his hope was rekindled when incoming leader Deng Xiaoping restarted university entrance examinations in late 1977, allowing all students to compete for a college place.

“For the first time there was a clear path in front of us,” said Hu, who went on to earn masters degrees at Tsinghua and Harvard, work for the International Monetary Fund, and lead Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in China. “The turmoil was behind us. A new era had come,” said the founder of Primavera Capital Ltd., a private-equity fund based in Beijing.

In the years that followed, Hu and hundreds of millions of others left the countryside and set up businesses in cities or went to work in factories that propelled China to become the world’s second-largest economy. Deng’s reforms, officially launched 40 years ago on Dec. 18 at a meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, precipitated one of the greatest creations of wealth in history, lifting more than 700 million people out of poverty.

But the changes also sowed the seeds of many of the problems China faces today. Two decades of growth at any cost under Presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao starting in 1993 saddled the nation with polluted rivers and smoggy skies, plus a mountain of debt. During that time, China became deeply integrated into the global economy, a trend that accelerated after it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

When President Xi Jinping assumed power in 2013, many hoped he’d turn out to be a leader in Deng’s reformist vein. But while Deng wanted his market-based reforms to make China rich, Xi has reasserted the control of the state in an effort to turn the country into a political and technological superpower.

“One of Xi’s overarching goals in terms of economic management is to effectively, if not formally, declare the end of the era of reform a la Deng Xiaoping,” said Arthur Kroeber, a founding partner and managing director at research firm Gavekal Dragonomics. Whereas Deng and subsequent leaders bolstered the role of private businesses in the economy and reduced that of the state, Xi seems to think the balance is now about right, Kroeber said.

Flouting Deng’s advice for China to lie low and bide its time, Xi went head to head with U.S. President Donald Trump and other world leaders, who were frustrated by years of Beijing stalling in opening its markets to foreign firms. China’s critics say domestic companies that are now aspiring for global dominance in technology and trade were raised on state subsidies or cheap loans while being protected from foreign competition.

The standoff has dealt Xi some of his first policy setbacks and an unusual upswing in public criticism in China. Even Deng’s son leveled a veiled rebuke in a speech in October, urging China’s government to “keep a sober mind” and “know its place.”

The confrontation comes at a critical moment for China as it tries to avoid falling into what economists call the middle-income trap, where per-capita income stalls before a nation becomes rich. Usually that happens because rising wages and costs erode profitability at factories that make basic goods like clothes or furniture, and the economy fails to make the jump to higher-value industries and services.

Only five industrial economies in East Asia have succeeded in escaping the trap since 1960, according to the World Bank. They are Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan.

To join them, Xi must oversee a transformation in China’s markets, injecting more competition in financial services, upgrading technology, and tightening corporate governance, while waging a trade war with a U.S. administration bent on containing the Asian nation’s rise. Xi’s challenge is compounded by an aging workforce, the mountain of corporate and local government debt, and an environmental clean-up that will take decades.

“No major economy that is not democratic has managed to surpass the middle income trap, so the odds are not in China’s favor even without the trade war,” said Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London. “Abandoning the Dengist approach has raised alarm bells in the West, particularly in the U.S. This makes the task much more difficult.”

Whether China makes it will depend on the legacy of those migrants and entrepreneurs who took advantage of Deng’s opening and set up private companies and conquered one manufacturing industry after another. Today, China’s private sector generates 60 percent of the nation’s output, 70 percent of technological innovation and 90 percent of new jobs, according to Liu He, Xi’s top economic adviser.

Shadow Banking

Many of those companies are feeling the brunt of Xi’s campaigns to deleverage the economy and battle pollution. A crackdown on shadow-bank financing has stifled a major source of funding during the boom years, while hundreds of thousands of small enterprises have been shuttered for despoiling the environment.

Their plight prompted an unprecedented push by policymakers this year to cajole banks into lending more to non-state companies, a campaign Xi endorsed by proclaiming his “unwavering” support for the private sector.

The policy response isn’t robust or effective enough and there’s a risk of a further weakening of business and investor confidence that triggers a vicious cycle, Hu said Sunday in a separate interview with Bloomberg Television. Policies toward the private sector are “incoherent ” with lip service in support of it and then more stringent regulations imposed on it, he said.

“What the government needs to do is to remove the straitjacket still stifling entrepreneurs,” he said. “There are still too many rules, stupid rules. The going is getting tougher. Hopefully that would shake off some of the bureaucratic complacency.”

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento