Germania. Manca il personale qualificato (e che parli il tedesco)

Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2018-07-22.

I dati di fatto sono inequivocabili.

*

Secondo Destatis, l'istituto di Statistica tedesco, a fine 2017 in Germania vivevano 82.741 milioni di persone, delle quali 9.576 milioni erano stranieri e 18.6 milioni di cittadini tedeschi ma con ascendente straniero.

A fronte di 792,131 nascita si aveva 910,902 morti: il saldo è negativo.

Ma questi dati aggregati possono trarre in inganno.

*

In Germania il 12.82% della popolazione è nella fascia 0 - 14 anni (5.3 mln  e 5.028 mln

e 5.028 mln  ).

).

Nella fascia 65 anni e più confluisce il 22.06% della popolazione.

Nella fascia lavorativa 24 - 65 anni vi sono in totale 44.348 milioni di persone.

Due fatti da evidenziare.

- Il rapporto anziani / giovani è invertito rispetto la norma: i vecchi son quasi due volte i giovani.

- I 9.576 milioni di stranieri sono quasi totalmente nella fascia lavorativa, per cui in essa vi sono 34.772 mln di autoctoni. Il rapporto stranieri / autoctoni è quindi 9.576 / 34.772 = 0.27. Circa un terzo della popolazione attiva è straniero.

*

Però il tasso di natalità di 8.6 nascite ogni 1,000 abitanti è retto prevalentemente dalla componente straniera. Se il tasso di fertilità globale si assesta all'1.45, quello relativo alle donne autoctone è inferiore allo 0.8.

Mentre per molti sarebbe facilmente comprensibile che gli autoctoni imponessero agli stranieri residenti di non proliferare, qui stiamo assistendo al fenomeno inverso. Sono gli autoctoni, le persone di etnia tedesca, a rifuggire dalla proliferazione, condannandosi così alla estinzione.

*

Tirando le somme per una sintesi, la popolazione tedesca autoctona sta avviandosi alla estinzione: nel volgere di qualche decennio essa sarà più che dimezzata.

Fatto questo bramato e voluto da alcuni, temuto ed avversato da altri.

Di sicuro emergeranno molti problemi.

Uno solo a mo' di esempio, sarà costituito dal fatto che a popolazione dimezzata dovrebbe corrispondere un consumo energetico dimezzato, e sono già in molti a domandarsi cosa se ne farà la Germania del surplus di centrali elettriche. Similmente, produzioni industriali di larga scala presuppongono una popolazione numerosa, così come un mercato interno è anche funzione del numero di abitanti abbienti. Infine, il vecchio non è certo portato ad investimenti aggressivi nel comparto produttivo: tipicamente predilige investimenti tranquilli che generino reddito.

Ma il vero problema attuale è la gestione del transitorio.

In Germania mancano, e sarà sempre peggio nel futuro, gli 'skilled workers', ossia persone con tedesco fluente e laurea breve tecnica.

Coloro che patrocinano l'immigrazione non sanno dare risposte al fatto che gli immigrati ben difficilmente parlano un tedesco fluente tale da poter essere inseriti come insegnanti negli organici della scuola, a fare i funzionari di banca, a ricoprire il ruolo di giudici, ed così via.

*

L'accluso articolo dello Spiegel ci riporta ai tempi delle armi segrete che avrebbero dovuto far vincere la guerra ai tedeschi: chi avesse espresso dei dubbi sarebbe stato impiccato su due piedi.

Resta il dubbio se l'articolista ci creda a ciò che ha scritto oppure semplicemente voglia prendere in giro il lettore.

L'articolista giulivo annuncia l'arrivo di 17 infermieri dalla Tunisia e considera risolto il problema.

Fate un test. Fatevi imprestare 40,000 euro da qualcuno e poi ditegli che gliene renderete 17. Forse la carrata di botte che vi somministrerà potrebbe essere maieutica.

Poi l'articolista si dilunga nell'elogio degli infermieri marocchini che ardono dal desiderio di servire i vegliardi tedeschi, coccolandoli e dando loro un cucchiaio di brodino.

L'articolista darebbe per scontato che i vecchi tedeschi parlino un arabo fluente, visto che i migranti non parlano certo tedesco.

Se Mr Hodgson fosse vissuto ai nostri tempi, invece che 'Piccolo Lord' avrebbe scritto dei migranti arrivati in Germania.

Questi migranti hanno lo spirito caritativo dei cherubini e passano il loro tempo nei cori angelici. Stando allo Spiegel, l'unico motivo di vita dei migranti sarebbe quello di fare i servi dei tedeschi.

Poi, quando il delirio allucinatorio passa, la realtà è del tutto differente.

p.s.

I vecchi bisognosi di ricovero in strutture idonee ammonterebbe secondo lo Spiegel a 2.9 milioni di persone.

Le rette di ricovero costano a partire dai 3,000 euro mensili, e solo una quota minima di persone può permettersi di spendere circa 40,000 euro all'anno per il gerontocomio. Conoscendo i tedeschi non si vorrebbe che alla fine prevedessero la 'soluzione finale dei vecchietti'.

Infine, tre milioni di vecchietti ricoverati necessiterebbero di circa 300,000 addetti. Un costo severo anche per la Germania: 17 tunisini sono una inezia.

German retirement homes are having trouble finding geriatric nurses. To resolve the problem, they're looking for help from abroad, recently expanding that search to Africa. Is it a good strategy? And for whom?

*

DREAMING OF GERMANY

Mohamed Ali Nefzi, 23, wants to live in a country where he can wear floral-print shirts without being stared at. A place where his mother won't ask him every week when he is finally going to get married and how many children he plans to have. For Nefzi, who goes by Dali, Germany is that place.

A tall man in suit-pants and suspenders, Dali Nefzi squints over the frames of his sunglasses into the glaring light on the beach of La Goulette in Tunisia. He's a registered nurse in his home country and until recently he worked as a paramedic for Pireco, the pipeline contractor.

Now, he's been chosen to participate in the German program Triple Win. He and 17 other people from Tunisia are to help alleviate the extreme shortage of geriatric caregivers in Germany.

Waves are breaking behind Nefzi on the beach of his hometown of La Goulette. Children are shouting as they play on the beach, calls drift over from the nearby basketball court, music pumps out of the cafés and the noise of TVs can likewise be heard from the marble sidewalks. He will miss his family and friends, Nefzi says.

------

"My goal is for all people to live with a smile on their faces."

------

THE DEAL

Nefzi took German lessons at the Goethe Institute in Tunis, paid for by his future employer, the Bavarian Red Cross (BRK). He only received his airline ticket after passing the test at the end of the course.

It costs the BRK at least 6,500 euros to recruit new caregivers from Tunisia. Their residency permit in Germany is directly linked to their job and candidates must first sign a contract with the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ), a development organization that works directly with the German government. The employer in Germany, in this case the Bavarian Red Cross, only takes over responsibility for the candidate once he or she receives additional training, completes another German language class and passes two state exams for geriatric care.

In total, each Tunisian recruited with GIZ help costs participating companies more than 100,000 euros. It's a lot of money, but the investment could pay off. After all, there are very few geriatric nurses in Germany who don't already have a job – and the situation has remained unchanged for years. Currently, an open geriatric nursing position remains unfilled for an average of 171 days, the worst average among all professions. At the same time, the number of people requiring old-age care continues to rise in a trend that is expected to last until 2060. The share of geriatric nurses from abroad has likewise been rising for years and is currently at 11 percent.

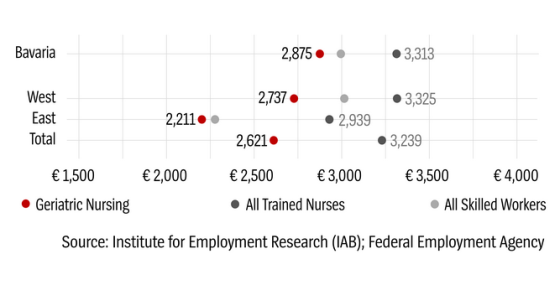

There is, succinctly put, an extreme shortage of people who want to become geriatric nurses – and especially not in rural Germany, where caregivers earn a gross salary of just 2,600 euros per month. That's what the social services division of the Bavarian Red Cross pays nurses who care for the elderly, which means Nefzi's salary is below the average for nurses in Bavaria. Furthermore, there is a significant gap between the pay received by home health nurses, the job Nefzi trained to do in Tunisia, and geriatric caregivers.

It's hardly surprising, then, that retirement homes are eager to keep their workers, and offer them all kinds of perks to convince them to stay.

Nefzi will be working in a retirement home in Olching, a bedroom community just northwest of Munich with 30,000 residents along with an old town center and a Catholic church.

If a caregiver falls ill, a replacement is immediately sent by a temporary work agency. Home management regularly invites caregivers to a free meal as a sign of gratitude. And instead of a simple meal in the Christmas season, the workforce most recently went to the theater and to a concert together.

------

"I find it so sad in Germany that the elderly have to live like this."

------

One of Nefti's future coworkers has something to say that sounds rather astounding coming from a practitioner of the geriatric nursing profession: "The work here won't crush you. You can't really complain."

It is, in other words, a triple win – a situation in which all sides benefit. Tunisia wins because it means there are fewer young people who need jobs, given the country's youth unemployment rate of 35 percent. Germany wins because the influx provides a bit of a respite given the shortage of care workers. And the geriatric nurse-in-training from North Africa wins because he can migrate legally to the EU and has a job in the German labor market. It is a dream that millions of others will never be able to fulfill.

But there is a significant shortcoming in the system. Germany is not spending money to transform otherwise untrained school graduates into geriatric care specialists. Rather, the Triple Win program removes already trained nurses that Tunisia needs as well.

Officials at GIZ say they adhere to the World Health Organization's declaration of intent, which holds that the needs of the country supplying migrant labor be considered as well. GIZ also says they are working closely together with the Tunisian labor office.

EUROPE WINS, AFRICA LOSES

"When everyone wins." That's the motto GIZ has chosen for its program aimed at recruiting foreign care nurses. But the truth is that Europe wins and Africa loses – at least if you ask those who are directly affected by the Triple Win pilot project in Tunisia.

Mounir Daghfous, a doctor and professor, leads the state-run emergency medical service in Tunis and was responsible for training Nefzi in emergency medicine, just as he has done for hundreds of others before him.

"We train them, and then they are lured away."

The four doctors and two caregivers who have already headed to Germany this year will soon be joined by others. A friend of Nefzi's – who is in the same GIZ program and who worked for Daghfous as an emergency caregiver – will be the next one to go.

Nefzi and the others are not part of the army of unskilled workers in Tunisia who have little hope of ever getting a job. On the contrary: Since quitting his job at Pireco one year ago, Nefzi has received four job offers. But, he says, he rejected all of them so he could fully dedicate himself to his German classes.

The rest of the 35 percent of young men and women who are unemployed will not receive any job training from Germany. They remain hopeless. In rural Tunisia, Islamists seek to attract the frustrated – and have historically had some success. Islamic State, which has now lost most of its territory in Syria, managed to attract an extremely high number of fighters from Tunisia and now the country is growing concerned about their return. Meanwhile, the UN's International Organization for Migration has catalogued a rapidly rising number of Tunisians seeking to make the dangerous Mediterranean crossing to Italy. In early June, more than 100 people lost their lives when their boat capsized not far from the port city of Sfax.

HELLO GERMANY!

On April 12, a sliding door in Terminal C of the Munich airport opens up and the geriatric nurse-in-training Dali pulls his huge suitcase through. Along with his personal belongings, the suitcase also contains Tunisian olive oil and cookies baked by his mother.

Nefzi's new boss Monika Wochnik and two of her employees are there to greet him. From the airport, they drive Nefzi to his new apartment and then to the supermarket Aldi, and they also help him with his official paperwork and to open a bank account. They give him a new bicycle, as well.

Nefzi simply smiles and says "danke!" before repeating the word a few more times. Danke, danke, danke. And then he is alone in his 45-square-meter (485-square-foot) apartment – freshly renovated and furnished. Everything is quite new, and the walls are even decorated with framed pictures bought at the furniture store.

On the drive back and forth through Olching, Nefzi gazed in wonderment at his new surroundings. All the cars, all the big houses, and everything so orderly. Now, he steps out onto his balcony on a warm spring afternoon and asks:

"Where are all the people?"

It's early May and things are going well for Dali Nefzi. His boss raves about his empathy and the warmth he shows to patients. He is so friendly with the elderly, she says, patiently lifting, washing and feeding them.

In Tunisia, caregivers must train for three years and ultimately receive about half the education of medical doctors. But before flying to Germany to take up jobs as geriatric nurses, Nefzi and the others were warned that the job is not highly valued in the country, that they are merely there to wash and feed the patients. Only after a year, once their qualifications have been recognized, would they be allowed to administer injections such as insulin. Furthermore, they were told, they would likely be working for female bosses – a warning that program directors felt was necessary for caregivers from Tunisia, a Muslim country.

Nefzi says that the basics of elderly care – washing patients, changing their diapers, turning them in their beds – are taken care of by families in Tunisia. "I find it so sad in Germany that the elderly have to live like this," he says. So he tries to compensate for the German coldness, doing things like taking the fragile Ms. Maier by the hand and saying: "Come along, Ms. Maier, let's go to the garden." "Well," says Ms. Maier in response, "what a good idea."

Nefzi quickly became friends with Andi, a wiry young man who was Nefzi's shift partner at the beginning. Andi enjoys dancing to heavy metal and has taken Nefzi into Munich a few times, including a visit to the Hirschgarten, the city's largest beer garden.

Over a snack and a wheat beer, Nefzi talks about his views on god and life in general. He refers to his outlook on religion as "Islam light." He keeps a copy of the Koran on his bedside table, to be sure, but he doesn't pray five times a day. Alcohol is a sin – but just a small one, he believes. Hard drugs, on the other hand, are haram – strictly forbidden. The same holds true for talking bad about someone behind their back.

Andi listens intently. "I liked you from the very beginning, but on that, we see things exactly the same way, you and me. And the fact that you can also enjoy a beer, that makes me really happy."

Nefzi's training isn't going quite as planned. He learned the basics of geriatric care a few years ago and has been helping out for the last four weeks at a station. But much of what is done in practice is new to him. His immediate superior says he'll have to continue his observation period for four additional weeks. That wasn't the plan at the beginning, his superior says, but it's also not a big problem.

Nefzi himself is ecstatic. "I enjoy my work," he says. "And everyone here is so nice, it's like my new family." A female coworker who hears the comment smiles warmly.

But then, in late May, there is a setback. Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting, has been underway since the 16th and Nefzi fasts the whole day through, for 18 hours at a stretch. And apparently, one of the 24 caregivers in the Olching team, a member of Nefzi's "new family," has a problem with that.

"Mr. Nefzi is facing a conflict."

Nefzi is accused of no longer washing women patients during Ramadan and of not responding to a resident's bell when he is breaking his fast in the evening.

The rumor makes the rounds for five days and Nefzi, because he has some time off due to a surfeit of overtime hours, cannot respond. "Mr. Nefzi is facing a conflict," says the woman who was so full of praise a few weeks before. "There is a need for consideration – on all sides." But not everyone in the team sees it that way.

"It's a lie," says Nefzi on the day he returns to work, defending himself during a team meeting. Yes, he is fasting, he says, but he is doing his job and jumping in when he is needed, just as he has always done. And, of course, he's still washing women because there aren't any men at his station at all.

Nefzi's superiors are embarrassed and the rumor cannot be confirmed. Just talk, apparently. Nothing to it.

But all the optimism that Nefzi brought with him from Tunisia has vanished. "Why do people do things like that? Nobody said anything to me directly, they're all so nice all the time." One of his coworkers, he says, even gave him dates at the beginning of Ramadan.

It is sinful to talk about others behind their backs, Nefzi believes. Apparently, at least one of his coworkers has a bit of repentance to do.

Shortly after the team meeting, Nafzi receives some good news. Adel, who he took German lessons with in Tunisia and who has now finally managed to pass his oral exams, will also be coming to Olching in June. The two will share the apartment at the edge of town.

That means that Mounir Daghfous' emergency care service in Tunis will once again be losing a paramedic. And the German geriatric care system will have another Tunisian employee.

If the two make good progress, Adel and Nefzi will advance to full geriatric nurse status instead of their current rank as assistants. That means they will earn full salaries, state recognition and, ultimately, permission to settle permanently in Germany.

Only then will it truly become clear who the winner is of Germany's search for nurses oversees.

e 5.028 mln

e 5.028 mln  ).

).

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento